by David Young, PA

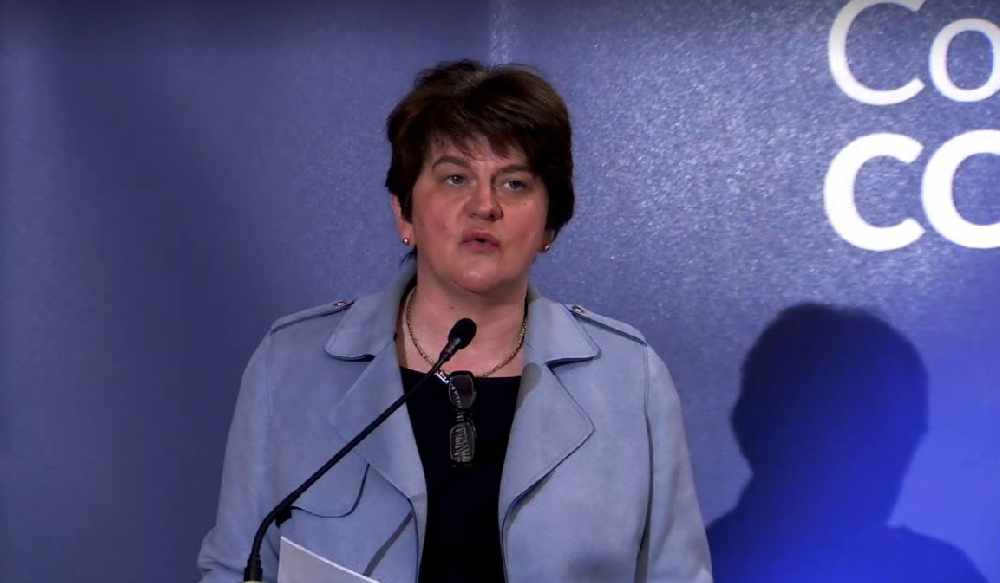

The internal push against Arlene Foster could be the final twist in a leadership rollercoaster that has been seldom free of controversy.

Her five years at the helm of the party have already witnessed some striking highs and lows.

She has been ousted as Stormont First Minister in a row over a botched green energy scheme; led her party through three torturous years of on-off negotiations with Sinn Fein to restore powersharing; and – only a month after devolution finally returned – found herself navigating a fragile coalition through a global pandemic.

But neither her handling of the Covid-19 emergency, the 36-month Stormont vacuum nor the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) furore are the reasons she is facing an internal revolt.

Instead it is Brexit’s Irish Sea border that could ultimately seal her fate.

And there is an irony in that – for the root of unionist and loyalist discontent at Mrs Foster’s role in EU exit process can be traced back to arguably her greatest day as DUP leader – the 2017 General Election.

That snap poll left the DUP’s 10 MPs as Westminster kingmakers and catapulted Mrs Foster to national prominence.

Striking a confidence and supply deal with the Conservatives saw her temporarily elevated to the top table of UK politics and raised expectations with the party faithful that the DUP would play a key role in shaping the Brexit deal.

So it proved, but not in the way Mrs Foster or her party envisaged.

DUP opposition was a key factor in the downfall of Theresa May and her “backstop” solution for dealing with the Irish land border issue.

Rejecting a softer Brexit, the DUP instead hitched its wagon to hardline Brexiteers. Boris Johnson famously wowed party delegates at the DUP conference in 2018 with a pledge never to create economic barriers in the Irish Sea.

A year later Mr Johnson, by then Prime Minister, agreed a Brexit deal that included the very thing he promised to resist – an Irish Sea border.

While those contentious arrangements – titled the Northern Ireland Protocol – enabled Mr Johnson to “get Brexit done” it also ensured a departure that left the region still wedded to many EU laws, as the rest of the UK broke free of them.

The resultant loyalist anger was to be anticipated. No surprise either that the DUP has been on the end of a lot of it.

First Minister Arlene Foster

DUP offices have been vandalised and graffiti denouncing the Irish Sea border often references the party.

The DUP did not devise the Protocol, and voted against it at Westminster, but many of their supporters believe a botched Brexit strategy by the leadership, including a sense they were hoodwinked by Mr Johnson, leaves them partly culpable for it coming into being.

While her internal critics remain fundamentally in favour of Brexit – albeit one that treats the UK as a whole – others outside the party have questioned the logic of Mrs Foster ever backing the Leave campaign in the 2016 referendum, given the likely constitutional problems it was likely to create.

Recent polls have suggested that resentment at the Irish Sea border could translate into an electoral battering for the DUP at next May’s Assembly election – an undoubted factor in the thinking of those who are backing the leadership push.

Mrs Foster’s tactics since the Withdrawal Agreement was sealed have also created concern among party rank and file.

While she is now a vocal critic of the Protocol, demanding its immediate scrapping, that was not always the case.

Last year she was insisting her job was to implement the Protocol and make it work, while also highlighting potential benefits of the Brexit deal for Northern Ireland. It was a position that dismayed many within her party and saw her come under significant pressure to adopt a more forthright approach.

She has now found herself in the awkward position of campaigning against the Protocol while leading a Stormont administration that has responsibility for implementing many of the processes and checks it requires.

Away from Brexit, there are also tensions within the DUP over social issues.

The long powersharing impasse saw Westminster intervene to introduce same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland and significantly liberalise the region’s abortion laws.

While Mrs Foster was not responsible for the London-imposed moves her party had long campaigned against; they happened on her watch.

Mrs Foster’s abstention in a vote on a proposed ban on gay conversion therapy last week appears to have further agitated the party’s fundamentalist grassroots.

The majority of her DUP Assembly colleagues voted against the motion, having failed to amend it to include specific mention of protections for religious practices.

That vote is further evidence of the tensions between Mrs Foster, a member of the Church of Ireland and former Ulster Unionist, and the more traditional Free Presbyterian wing of the DUP, who perceive her as potentially too moderate on some social issues.

While far from a social liberal, Mrs Foster has tried to distance the party from its “Save Ulster from Sodomy” past.

In 2019 the party saw its first openly gay candidate elected to a local council and in the coming weeks Mrs Foster is set to break new ground by meeting with LGBT advocacy organisations.

There are other issues of friction within the DUP.

Many of her critics claim Mrs Foster has lost touch with her party’s base. They point to a perceived aloofness in dealings with other elected representatives and a sense that key decisions are made by a tight group of confidants and advisers.

In regard to powersharing with Sinn Fein, the deal to restore devolution included a DUP concession to legislate for Irish language protections.

Some hardline members are infuriated that the party faces the prospect of having to pass Irish language laws at Stormont at the same time as the Northern Ireland Protocol is, according to them, undermining their place in the UK.

For these DUP members, it all amounts to an insidious slide towards a united Ireland that can only be halted by a more robust leadership team.

Woman assaulted while jogging in West Belfast

Woman assaulted while jogging in West Belfast

Leading loyalist Winston Irvine sentenced to 30 months for firearms offences

Leading loyalist Winston Irvine sentenced to 30 months for firearms offences

Rescue operation to free 40 cows after lorry overturns on motorway

Rescue operation to free 40 cows after lorry overturns on motorway

New date set for trial of former DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson and wife

New date set for trial of former DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson and wife